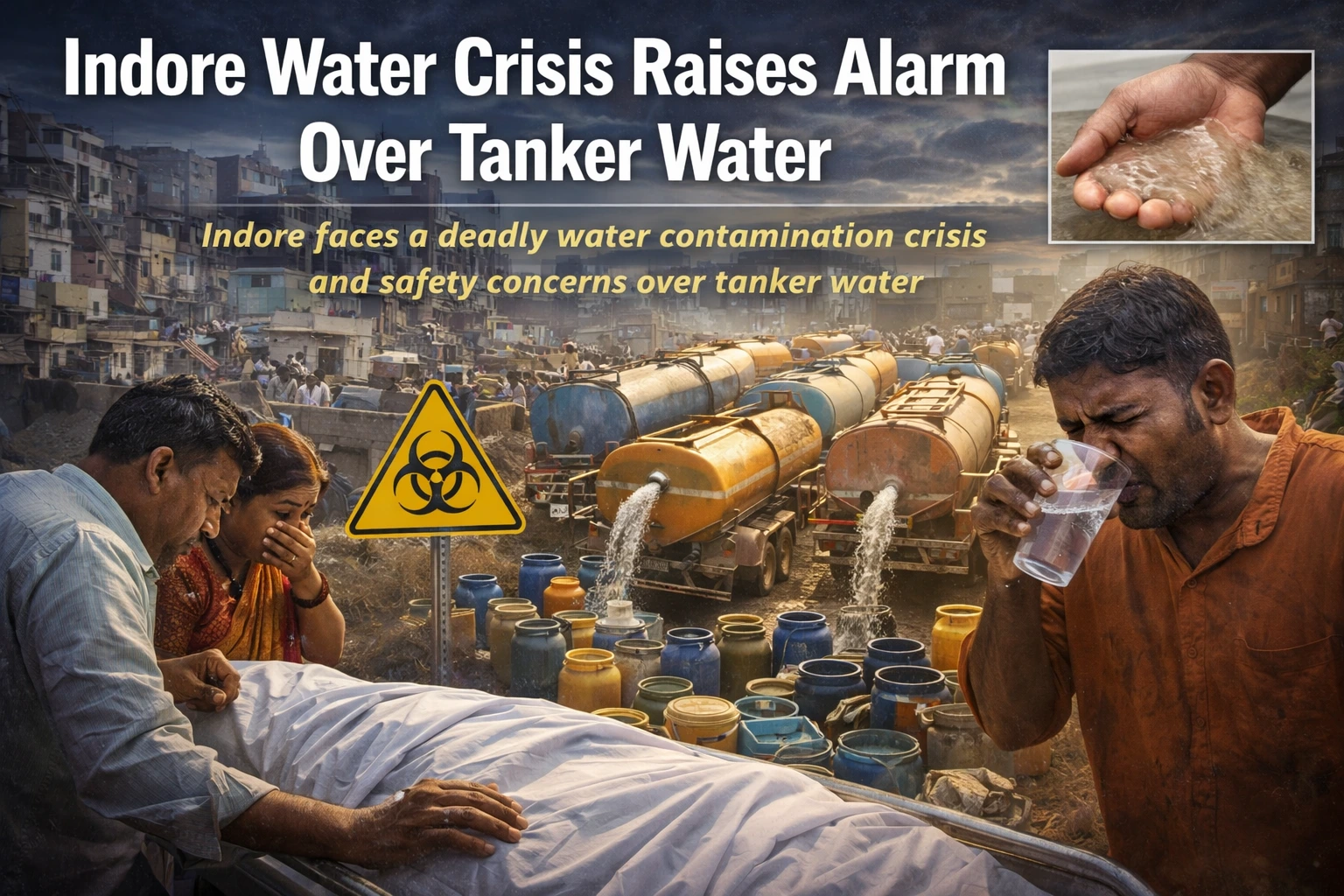

Once celebrated as India’s cleanest city, Indore now faces one of its most serious public health emergencies in years as contaminated municipal drinking water in the Bhagirathpura area has been linked to dozens of deaths and widespread illness, raising urgent questions about infrastructure oversight, emergency preparedness, and the safety of alternate water supplies such as tanker water.

Outbreak and Scale of the Crisis

The crisis started at the end of December 2025, when people of Bhagirathpura reported strange alterations in their tap water, foul smell, discoloration and bitter taste. After days, individuals who took the water experienced severe vomiting, diarrhoea, signs of dehydration and fever that are common with waterborne illness. Residents rushed into hospitals in the region, overloading them.

Determination of contaminated municipal water as the cause of a diarrhoea outbreak was later confirmed in a laboratory after sewage reached the drinking water supply when a leaking pipeline passed through a police outpost in Bhagirathpura. Authorities claimed the pollution was of bacterial origin, which is in line with sewage pathogens.

At least 10 deaths are confirmed, and hundreds of people are still hospitalized. Although the official numbers differ, the authorities affirm that many more are ill. Local reports and community allegations are that the real number could be much greater, with even the young children and the aged being victims.

Breakdown of Response and Infrastructure Failure

The outbreak has revealed great weaknesses in civic infrastructure and responsiveness. According to the residents, they had reported foul-smelling and discoloured water days before the crisis took a turn and no effective measures were taken in time. The breaking point -a main pipeline that was leaking with sewage and drinking water was possibly avoided in case regular maintenance and inspection had been done.

The political backlash has been rapid. The municipal commissioner of Indore was fired, and high-ranking civic officials were suspended by the government of Madhya Pradesh. Chief Minister Mohan Yadav said that laxity in the health affairs of the citizens will not be entertained anymore.

The involvement of the High Court has a part to play too. The High Court of Madhya Pradesh directed the authorities to establish a continuous supply of clean drinking water and provide the most available medical care to affected persons, and to report and hold them accountable periodically.

Tanker Water: A Solution with Mixed Trust

During the short-term response, the government dispatched water tankers to the impacted regions to supply them with alternative drinking water. This was to be used as a temporary solution to enable residents to have access to potable water during the pipeline repair and flushing processes.

However, a good number of locals are still not ready to use tanker water. The decades of unreliable municipal provision and the overall distrust toward the quality of water have led to the fact that the people are suspicious of any unverified water. Certain families have been reported to shun even tanker water to drink because they fear that it may also be contaminated, particularly where the sources of tankers are not officially certified.

The use of boiled water before experts and health authorities several times as a way of minimizing the chances of bacterial infection, as well as being a prerequisite until water safety has been formally established. They also suggest the use of sealed bottled water or water whose origin has been tested as safe to infants, older people and those with a weakened immunity.

Impact on Public Health and Society

The social price of the crisis is pathetic. The families in Bhagirathpura are still grieving the loss of their relatives due to curable ailments, including babies whose conditions deteriorated in a very short time. Another common personal narrative was that of the death of a six-month-old child, whose family did not want compensation from the government, and they could not give any sum of money to value the loss.

The hospitals are receiving reports of increased cases of severe dehydration and diarrhoea, which manifest the severe health effects of consuming contaminated water. The children, older people, and people with pre-existing conditions have been the most affected in this outbreak.

Government and Judicial Measures

In response to widespread outrage, the state government has acted disciplinarily against civic officials and has pledged to make changes to water safety measures. The orders issued by the High Court are expected to enhance accountability whereby the municipal authorities must uphold the standards of water quality, as well as repairing the damaged infrastructure, and also conducting regular testing with publicly available outcomes.

The state leaders have also committed to paying all medical bills of the affected as well as increasing emergency medical and sanitation services in the impacted localities.

Critical Infrastructure and Governance Lessons

This tragedy underscores a stark reality: even cities with strong reputations for cleanliness can suffer catastrophic failures in essential public services when oversight lapses. Indore’s water crisis highlights several systemic weaknesses:

- Aging infrastructure that is vulnerable to leaks and contamination.

- Insufficient monitoring and rapid response to public complaints.

- Absence of open water quality reporting to the citizens.

- Sewage and sanitation holes directly affect the drinking water.

Experts argue that ensuring water safety requires more than emergency responses; it demands predictive maintenance, real-time water quality testing, and citizen-centric governance that treats safe drinking water as a basic human right rather than a peripheral utility.

Editorial Insight: A Wake-Up Call for Urban Water Safety

As an experienced news editor covering public health and urban governance, this crisis in Indore serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of essential services — even in places once praised for sanitation excellence. The consequences of contaminated drinking water are immediate and devastating. They reach far beyond hospital beds and headlines; they break families, erode community trust, and expose governance failures at multiple levels.

Public infrastructure must be proactive, not reactive. Residents’ early complaints about foul water should have triggered targeted testing and pipeline inspection long before illness began to spread. The failure to act highlights a dangerous complacency in civic management where visible cleanliness masks invisible vulnerabilities.

Trust in tanker water — an emergency substitute — is understandably low because it is perceived as an ad-hoc solution without guaranteed quality standards. This incident should prompt authorities to establish certified tanker water supply protocols, supported by regular testing and clear labeling of safe drinking sources.

Looking ahead, India’s urban centers must adopt robust water safety frameworks that include stringent quality monitoring, transparent public reporting, rapid leak detection systems, and emergency preparedness plans that do not rely on ad-hoc responses alone. Only then can cities ensure that access to safe drinking water is truly universal and resilient to failures that can turn everyday water into a public health nightmare.